BULAWAYO — Minority groups in Matabeleland have intensified programmes aimed at promoting their previously marginalised languages in the wake of the adoption of the new Constitution of Zimbabwe in June this year.

BULAWAYO — Minority groups in Matabeleland have intensified programmes aimed at promoting their previously marginalised languages in the wake of the adoption of the new Constitution of Zimbabwe in June this year.

The new supreme law, which repealed the Lancaster House charter, accords official status to 16 languages.

Most of them are spoken in Matabeleland South and Matabeleland North provinces.

The old constitution only recognised English, Ndebele and Shona as the official languages of Zimbabwe.

Section 6 (1) of the current Constitution reads: “The following languages, namely Chewa, Chibarwe, English, Kalanga, Koisan, Nambya, Ndau, Ndebele, Shangani, Shona, sign language, Sotho, Tonga, Tswana, Venda and Xhosa, are the officially recognised languages of Zimbabwe.”

Under the same section, 6 (4), the supreme law stipulates that the State must promote and advance the use of all languages used in Zimbabwe, while creating conditions for their development.

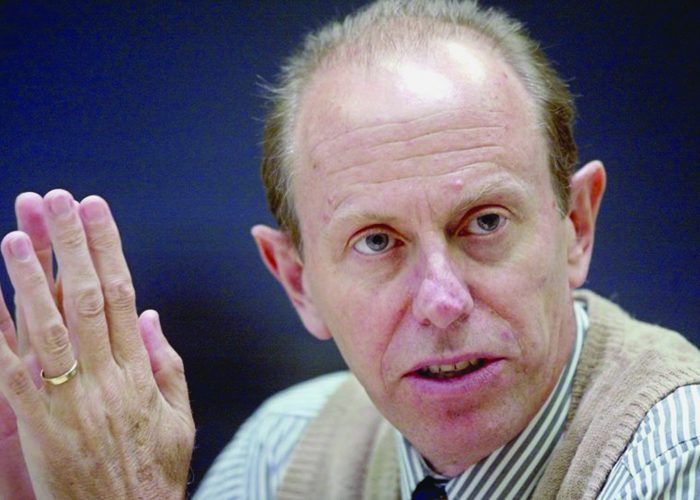

Outgoing Education Minister, David Coltart, said he expects the incoming government to honour the language policy by ensuring that all the local languages are taught and examined in schools.

In Matabeleland, various lobby groups are ratcheting up pressure on government to set the wheels in motion.

One of the groups working flat out to promote minority languages is Basilwizi whose main objective is that of facilitating Tonga language orthography harmonisation.

Frank Mudimba, head of the programme, said Basilwizi promotes Tonga language being spoken predominantly in Binga.

“This was achieved through collaboration with University of Zambia and University of Zimbabwe (UZ) in February 2013. Lusumpuko, a secondary school textbook series, has also been produced with our help and is being used in the lower tiers of secondary education,” said Mudimba.

Basilwizi and its partners are now working on the Ordinary Level set of Tonga textbooks and Tonga novels.

Among other things, the organisation has also facilitated the writing of Tonga language at Grade 7 since 2011.

The Koisan people are also trying hard to revitalise their dying language.

Last month, they convened at Gariya Dam in Tsholotsho to celebrate the United Nations International Day of the World’s Indigenous People.

The day’s objective is to promote non-discrimination and inclusion of indigenous peoples in the design, implementation and evaluation of international, regional and national processes regarding laws, policies, resources, programmes and projects.

The Koisan, found in Tsholotsho and Bulilima and with a population of about 2 000, have since formed the Creative Arts and Education Development Association (CAEDA) to document and promote their language.

CAEDA director, Davy Ndlovu, said their language was not Koisan as it is referred to in the new Constitution but Tshwao.

He said they had tried to no avail to bring that to the attention of Constitutional Parliamentary Select Committee, which presided over the writing of the new charter.

Ndlovu said the Koisan people would still pursue the same issue with the incoming ZANU-PF government.

Tshwao is fluently spoken by only 15 elderly people aged between 65 and 97 while the rest spoke a diluted version.

“What we are doing at the moment to preserve the language is recording those few elders as they speak so we can come up with the vocabulary that we can later pass on to children. It’s quite interesting because the younger generation is also showing interest in learning the language,” said Ndlovu.

“We have engaged the UZ which is assisting us with documentation. The other problem is that the education system does not cater for the San. There is no-one among the San who is educated enough to be able to teach this language in schools,” he added.

Ndlovu said they were having challenges with resources to expand their programmes, adding that their children who were fortunate enough to go to school were learning Ndebele and fast losing touch with their own culture.

Former Ward 15 councillor for Mangwe, Thandiwe Moyo, of Mphoengs where SeTswana is spoken, said they would lobby their newly elected legislator, Obedingwa Mguni, to push for the promotion of that language in the area bordering Botswana.

“We are saying since at our homes we speak SeTswana to our children, it would be good if that same language was taught at our schools and be promoted in line with the new Constitution,” Moyo said.

Kalanga Language and Cultural Development Association (KLCDA) chairperson, Pax Nkomo, said while the other so called minority languages were being marginalised locally, they were being promoted outside Zimbabwe save for Kalanga which was suppressed by the colonial Rhodesian government.

He cited Venda, Sotho and Xhosa as being taught at colleges and universities in neighbouring South Africa, and Tonga in Zambia.

He said the imposition of Ndebele chiefs on the Kalanga people contributed to the neglect of the language predominantly spoken in four out of seven districts of Matabeleland South namely Bulilima, Mangwe, Matobo and Tsholotsho.

“We are not going to let our language die and we therefore challenge the incoming new government of Zimbabwe to give Kalanga language affirmative action so we can liberate our culture which was suppressed,” said Nkomo.

He said the BaKalanga themselves must arise and champion that cause and not wait for the government to take the lead.

Nkomo, however, said despite the challenges primary school textbooks had been printed from the Education Transition Fund and were at a UNICEF warehouse awaiting disbursement to schools.

Some schools in areas where Kalanga is spoken are already teaching the language which is yet to be examined by the Zimbabwe Schools Examination Council.

Zimbabwe Indigenous Languages Promotion Association (ZIPLA) chairperson, Mareta Dube, said they had successfully lobbied the Ministry of Higher and Tertiary Education to consider training teachers in those languages. Joshua Mqabuko Polytechnic is already training teachers for Kalanga, Sotho and Venda.

“We hope that the United College of Education will follow next year,” she said.

Dube said ZILPA which is currently focusing on six languages — Sotho, Venda, Kalanga, Nambya, Tonga and Shangani — had financial constraints. For example, Sotho books remain soft copies at Longman-Zimbabwe due to lack of funding to have them printed.

Dube said they needed finances to gather relevant literature in the languages for students and future generations.

She appealed to the incoming government to consider importing skills from countries which have already been teaching those languages or introduce scholarships for Zimbabweans to go and train as lecturers and teachers in those same countries.

Kalanga cultural activist and author, Ndzimu-unami Emmanuel Moyo, said he was sceptical of government’s political will to advance minority languages, adding that there were some elements within political parties that were against their promotion during the constitution-making process.